The 4% Problem: Why Nigeria’s Parliament Needs Gender Quotas

Recently in June 2025, ahead of the Nigerian by-election, Hon. Amina Dogon-Yaro, a first-time woman aspirant for the seat of Garki/Babura Federal Constituency in the House of Representatives from Jigawa State in the northwest of Nigeria. She went to her constituency in Jigawa State, surrounded mostly by women volunteers and well-wishers. She had worked tirelessly door-to-door canvassing, attending community dialogues, and participating in late-night strategy sessions. Yet, despite her passion, voluntary resignation from her more than 20-year career job and personal good track record, her party leadership pressured her to step aside for a male contender, citing “winnability”. Her story is not only one; it is the silent reality of hundreds of Nigerian women who aspire to political office but face structural, financial and cultural barriers at every turn.

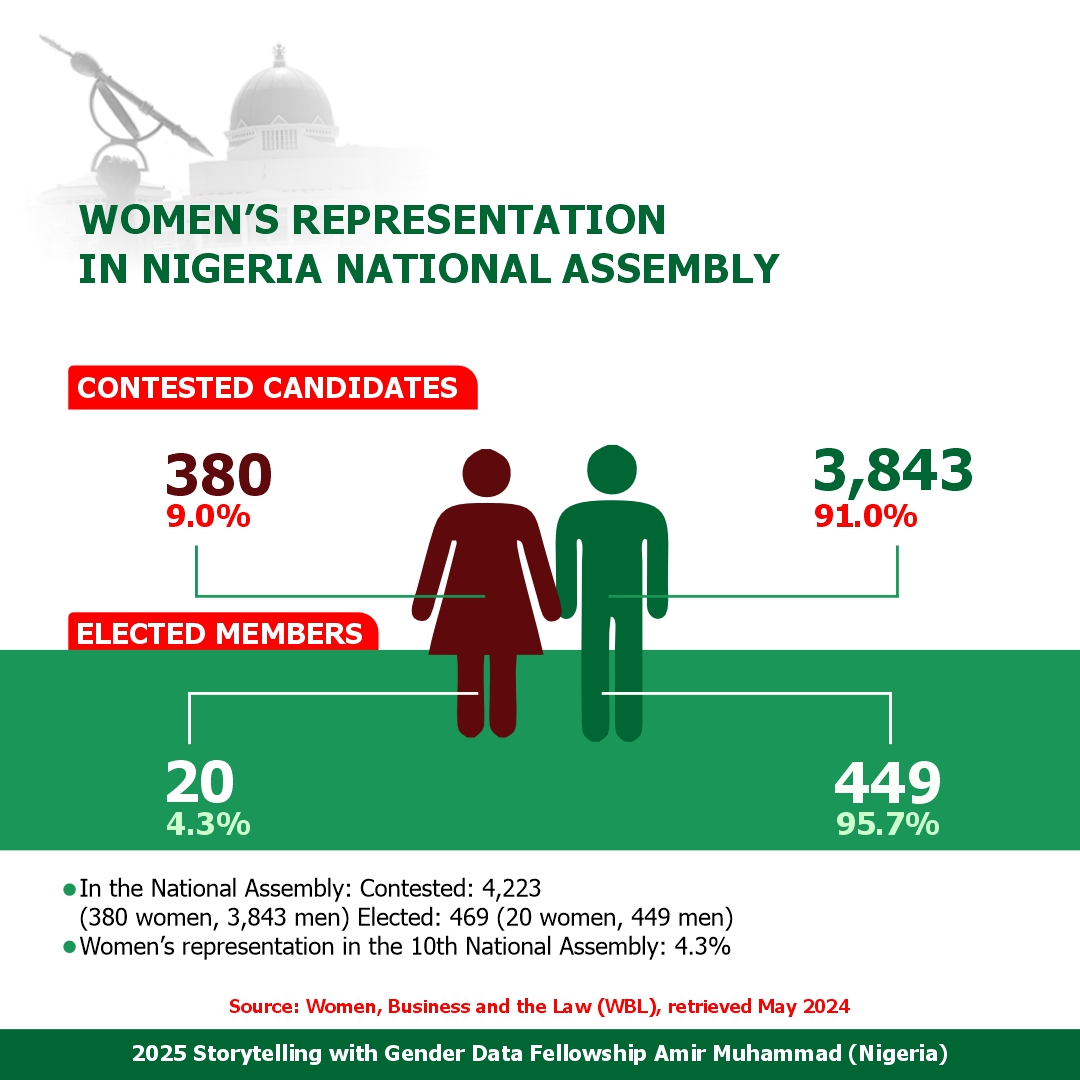

According to the 2024 SDG Gender Index by Equal Measures 2030, Nigeria ranks 127 out of 139 countries and 26 out of 36 regional countries with an overall score of 47.4 and just 40.22 for SDG 5 (Gender Equality) in 2022. It was also found that female political representation in the 2015 and 2019 elections in Nigeria was negligible relative to the approximately half of the population they constitute, with 2,970 women on the electoral ballot, representing only 11.36 percent of elected candidates across the country said by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

Another shocking result? In Nigeria’s 10th National Assembly, women also occupy just 4.2% of all seats. Out of 469 lawmakers – 109 senators and 360 representatives – only 17 are women. Put plainly: 96 out of every 100 lawmakers in Nigeria are men. This is “The 4% Problem”.

Why It Matters

Beyond numbers and statistics, the absence of women in decision-making has real consequences for individuals, families, and entire communities in Africa generally.

Here are some personal stories that show what Nigeria risks by keeping women out of leadership, published by PLAC (2024):

“I sat in meeting after meeting, presenting the data, sharing the heartbreaking realities of preventable childbirth complications, but there were no women in the room to fight for these mothers. Policies were made by men who did not understand the urgency.”

In countries where women lawmakers drive policy, maternal deaths have dropped by over 40%, but in Nigeria, the absence of women in power has kept funding for maternal health dangerously low.

“They told me to bring my husband or father to guarantee my loan. They didn’t care that I had been running this business successfully for years.”

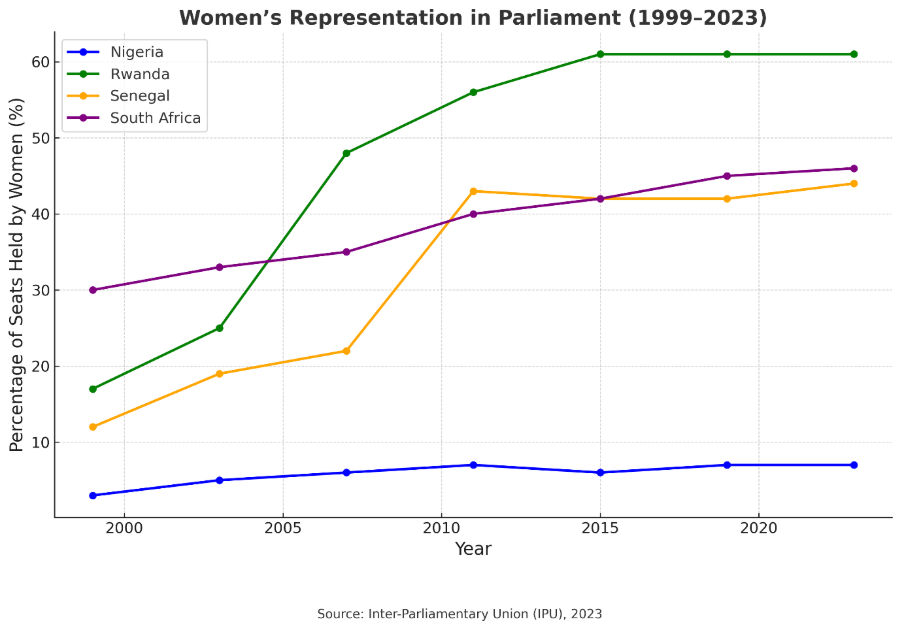

In Rwanda, where women hold 61% of parliamentary seats, business policies have changed to ensure equal access to funding, leading to a 20% rise in women-led businesses. But in Nigeria, the exclusion of women from economic policy-making means many talented female entrepreneurs never get the opportunity to scale their businesses.

“She cried and begged me to let her finish school,” said her teacher. “But there was no law to protect her, no woman in power to champion her rights.”

Countries like Tunisia and Senegal, where women hold a significant percentage of parliamentary seats, have passed strong laws protecting girls from early marriage. Yet Nigeria still lacks the political will to enforce child protection laws, leaving many girls vulnerable.

“They told me I had no say. That I should leave my late husband’s property. That this is how it has always been.”

In countries like Ethiopia and Uganda, where women hold at least 30% of parliamentary seats, laws have been enacted to protect widows’ land rights. But in Nigeria, with only 3.6% of lawmakers being women, thousands continue to be dispossessed.

Therefore, the exclusion of women from lawmaking is not just a rights issue; it is a governance issue. This is because evidence shows that when women are at the decision-making table, outcomes improve. Unfortunately, Nigeria is losing out on these benefits. Policies are being shaped in a chamber where half the population has only 4% of the representation.

Why the Numbers Stay Low

- Political Parties: Nomination processes heavily favour men, with women often pressured to step down.

- Campaign Financing: Women face greater financial barriers, with limited access to funding networks.

- Cultural Barriers: Persistent stereotypes question women’s leadership capacity.

- Weak Legal Frameworks: Unlike Rwanda and Senegal, Nigeria has no binding gender quota law.

What Can Be Done

Other countries show us the way:

- Rwanda’s constitutional quota ensures at least 30% women’s representation, but in practice, women now hold more than 60%.

- Senegal’s parity law requires parties to present equal numbers of male and female candidates.

- South Africa’s party quota system (voluntary, led by the African National Congress) boosted women’s representation past 40%.

Nigeria can do the same.

To tie these statistics to the lived reality of female leadership, Senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan (Kogi Central Senatorial District) shared powerful insight from her own experiences:

“Politics is extremely dangerous in Nigeria. In Nigeria, you can’t be gentle as a woman.”

Her words illustrate the challenges women face, not just institutional but deeply emotional and personal.

When women lead, communities flourish. Senator Ireti Kingibe (FCT Abuja), Chairperson of the Senate Committee on Women Affairs, emphasised this when advocating for a Reserved Seats Bill:

“When women are part of decision-making, we see stronger communities, more inclusive legislation, and better outcomes in health, education, and peace-building. Representation matters—not just symbolically, but substantively.”

These testimonies make clear that it is not just about filling numbers; it’s about justice, equity and communal well-being.

The Solutions

- Pass a gender quota law requiring at least 30% of party candidates and elected seats to be women.

- Strengthen campaign financing frameworks to provide women equal access to resources.

- Partner with civil society and the Ministry of Women Affairs to track and enforce compliance.

The Way Forward

Nigeria has committed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 5: Gender Equality), but at the current pace, true inclusion in politics is generations away. Without reform, the lower participation problem risks becoming a permanent stain on Nigeria’s democracy.

The time to act is now. Lawmakers, party leaders, civil society organisations, and citizens all have a role to play in demanding a more representative democracy.

As Hon. Amina herself put it, after losing her nomination bid: “It is not just about me; it is about the millions of Nigerian girls who deserve to see women leading at the highest level. If they don’t see us there, how will they believe they can get there?”

Her words echo louder than the statistics. The 4% problem is not just a number; it is a call to action.

This story was developed by Amir Muhammad as part of the 2025 Storytelling with Gender Data Fellowship, a six-month programme by Equal Measures 2030 supporting young advocates to transform gender data into compelling stories for change. Learn more about this fellowship here: https://equalmeasures2030.org/blogs/introducing-our-2025-storytelling-with-gender-data-fellows/