The key to Africa’s economic recovery? Pan-African Feminist alternatives.

By Nadia Ahidjo, Africa Programs and Partnerships Lead & Esme Abbott, Communications Coordinator

To ensure Africa’s economic recovery is just and sustainable, African women must be front and centre of growth and economic policies. This extends beyond the optics and requires meaningful engagements in decision, discussions, and implementations of these policies.

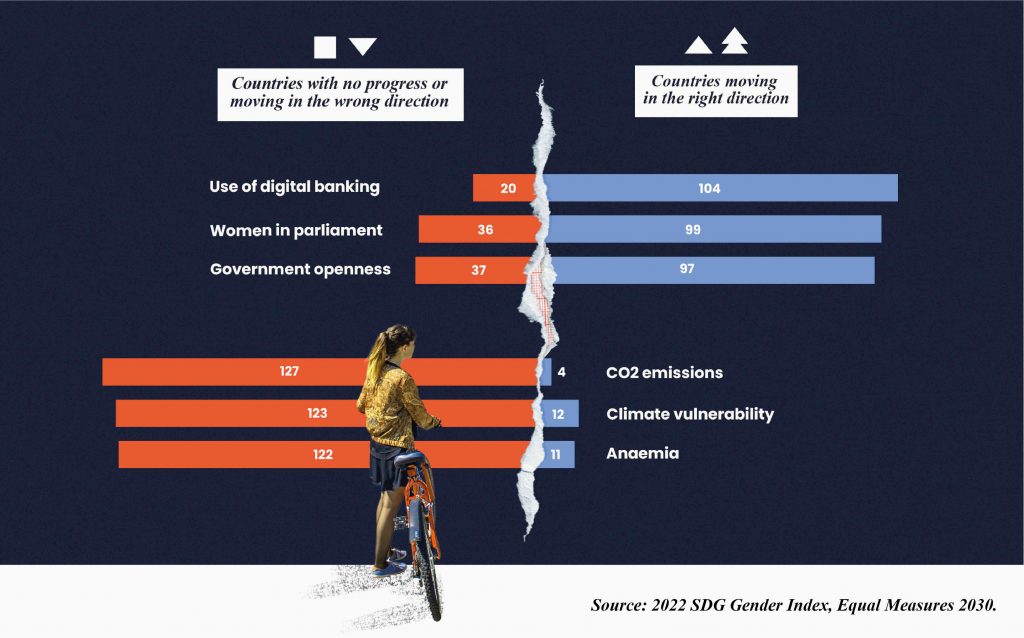

On certain aspects, especially around women’s political leadership; data from the EM2030 2022 SDG Gender Index reveals that countries like South Africa, Rwanda, Mozambique, and Ethiopia have far greater representation of women in their senior Government and Ministerial-level positions than countries like Denmark and Norway which are often touted as beacons of gender equality.

Significant gains have also been made across the continent in terms of women’s use of digital banking and access to the internet (key gender indicators of SDG9 – innovation). Women in Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe are more likely to have used digital banking in the last year than women in Argentina, Indonesia, or Mexico. This is a step in the right direction but should be nuanced when it comes to translating into meaningful changes in women’s livelihoods.

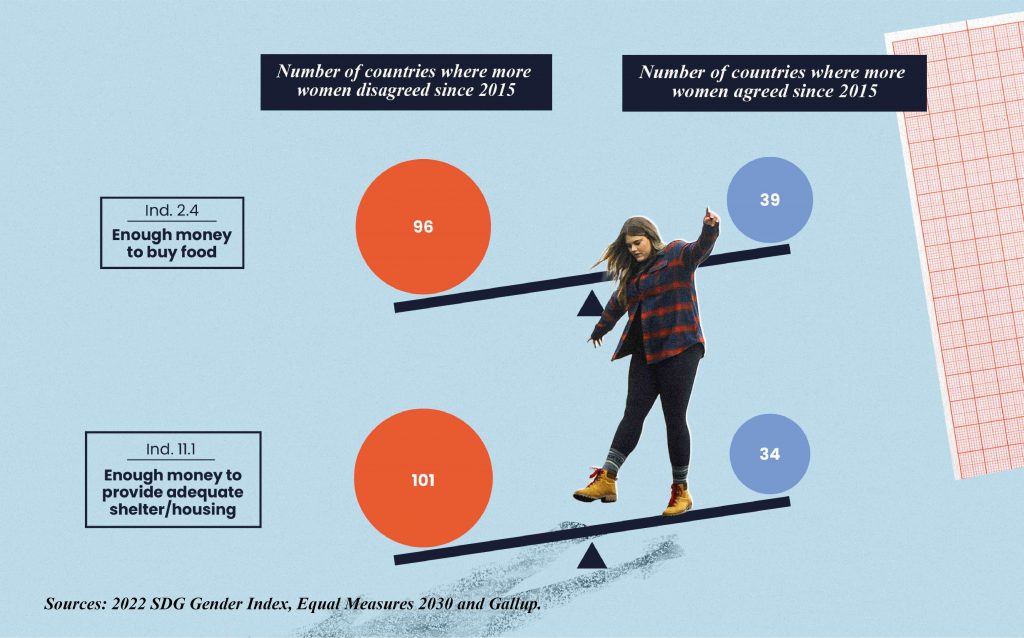

Poverty remains another underlying barrier across Africa and has intensified under the pressure of the pandemic which wiped out more than four decades worth of progress globally according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Report. Yet even before the pandemic nearly 70% of women across Africa had concerns about their household income and whether it was sufficient for their families’ needs – a concerning number that was already growing between 2015 and 2020.

Austerity measures have become the ‘go-to’ option in times of crisis but even the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) own research shows that austerity measures increase poverty and inequality. Women are over-represented in public-sector, informal, and domestic care work, all of which are threatened by austerity measures. For many low-income countries, or those in economic crisis, austerity is not a matter of choice, but a requirement to access grants and loans.

According to research by Oxfam, 76 out of the 91 IMF loans negotiated with 81 countries since the beginning of the pandemic push for cuts in public services, even in the very healthcare systems that are vital during a health crisis. Avoiding austerity measures will not only help African countries challenge patriarchy but also the neo-colonial practices that have stifled economic development.

Countries across Africa cannot fully recover if these challenges are not put at the heart of economic policies and plans for growth. To do this, we must apply a Pan-African feminist1 and intersectional lens to all policies, ensuring that they resist neoliberal and patriarchal economic values and acknowledge the complex intersections of identity, race, class, gender, and culture. Without understanding how inequalities combine and accumulate, it is hard to identify the problems or the solutions, and policies will fail to provide the sustainable growth needed.

A lack of timely, disaggregated data, results in policies that are neither intersectional nor inclusive. Not only will they fail to reach those most in need, but we will not have the evidence needed to point to their failure. Thirteen African countries were not included in the EM2030 2022 SDG Gender Index due to a lack of gender data.

Major gaps continue to exist around unpaid care, domestic work and the gender pay gap – areas where sharp gender inequalities exist. These gaps make it harder to identify the needs of those most affected, whilst also resulting in a lack of accountability and economic policies that aren’t accountable, easily become ineffective, or worse, exploitative. Instead of slashing budgets, money should be invested in public services and public infrastructure and managed in a gender-responsive way (aided by the collection of gender data).

Various African countries have written strong gender parity quotas into legislation but without accountability and enforcement they lack the practical application. It is not enough for seats to be open to women if the system is still dominated by a patriarchal culture that has historically worked to, and profited from, their exclusion.

FEMNET have been clear in their demands for government policies to acknowledge intersecting discriminations and challenge oppressive systems such as patriarchy, capitalism, and neo-colonialism.

When we adopt a Pan-African feminist lens, we place African girls and women at the centre of policies, and we start challenging these systems by questioning the power dynamics and privileges they impart. We raise questions about control of assets and resources, about cultural norms and values, and about power.

Denouncing neo-colonial ideas that perpetuate inequality and instead centering African women and girls will lead to a recovery that is not just full, but equitable, and sustainable – important characteristics in a world that is set to see further shocks.

1.We understand this as defined by the African Feminist Forum which places patriarchal social relations structures and systems which are embedded in other oppressive and exploitative structures at the centre of our analysis.