Equal Pay Day is still needed, here’s why!

Do we really need an Equal Pay Day? Things are getting better, aren’t they? Despite progress in some countries, the gender pay gap still persists.

Written by Charlotte Minvielle, Head of Business Development and Gabrielle Leite, Gender Data & Insights Analyst

Across the globe, women are paid an estimated 20% less than men. This injustice is brought to attention each year on International Equal Pay Day, designated by the European Commission as November 15th this year. This date symbolizes the extra time women on average must work to catch up with men’s earnings of the previous year, or in other words, the point in the year when women start working for free. Since the gender pay gap varies significantly from country to country, so does the designation of Equal Pay Day.

The global picture

Globally, very little progress has been seen in the reduction of the gender pay gap. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report for 2023, which covers 146 countries, the overall score changed from 68.1% to 68.4%, a meager improvement of just 0.3 percentage points compared to 2022. The countries with the greatest increase were Liberia with a score increase of 5.1%, Estonia with +4.8% and Bhutan with +4.5%.

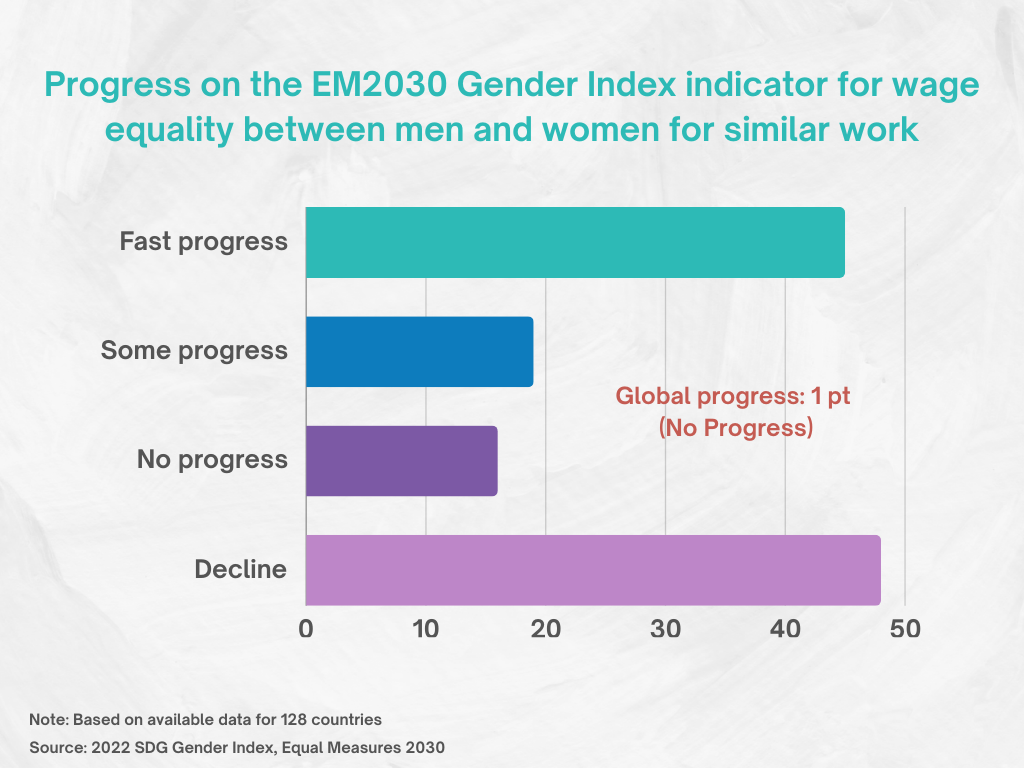

Equal Measures 2030’s SDG Gender Index also shows us that globally, wage equality between men and women for similar work stagnated between 2016 and 2020. Among 128 countries with available data, just 45 were making fast progress, while 19 countries made some progress, and 16 showed no progress. Alarmingly, 48 countries have declined, with the 3 largest decreases coming from Sub-Saharan countries: South Africa with -14.6, Mauritania with -12, and DR Congo with -10.7.

Addressing social norms

This year, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Claudia Goldin, recognizing her ground-breaking work in demystifying the root causes of the gender pay gap. Goldin highlights how gender disparities in earning in the past could primarily be explained by educational attainment and occupation choices. However, today the earnings gap for women and men in identical position widens most when women give birth to their first child.

A UN Women and ILO study also found that childbearing, more than marriage, affects labour force participation. Women are more likely to be outside the labour force when they marry and have children, especially young children. This is much more pronounced when they have at least one child under 6, underscoring the pivotal role of unpaid caregiving and household labour divisions.

Women on average carry out at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men. Gender stereotypes and social norms often trap women in low-skilled, low-paying jobs. To move towards equal pay, we must address the routine devaluation of women’s work, particularly in professions predominantly occupied by women such as nursing, elder care and education.

Truly eradicating the pay gap though, demands a multifaceted and intersectional approach, acknowledging that women of color, women with disabilities, lesbian, and trans women face additional and unique barriers to equality in the workplace. In 2020, Black women in the United States were paid a mere 58% of what non-Hispanic white men received. Addressing these systemic inequalities is essential to close the gender pay gap.

Legislation for systems change

According to an internal report by HP quoted in Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, women applied for roles only when they believed they met 100% of the qualifications listed for the job, while men applied if they thought they could meet 60% of the job requirements. Previous studies (and public opinion) have also suggested that men are often better at asking for salary increases.

However, recent research has highlighted that women often do ask just as frequently, they just don’t receive as frequently. Concerningly, studies have also shown that when people believe that women negotiate less, they are less inclined to support policies to reduce the gender pay gap. The onus for workplace equality cannot be laid on individual employees and the confidence to negotiate salaries; it requires systemic transformation.

The ILO found that pay transparency measures can be a powerful tool in exposing pay differences between men and women and identifying the underlying causes. They can provide workers with the information and evidence required to negotiate salaries and the means to challenge potential pay discrimination.

In 2022, the European Parliament made a landmark decision, mandating all European companies to disclose potential gender pay gaps. While transparency is an important step in the right direction, it can fall short without robust enforcement mechanisms to support it.

Transparency measures have been found to be more effective in countries with higher rates of unionization. In Belgium, where almost half the workforce belongs to a trade union, the gender pay gap halved, from 10% in 2010 to 5% in 2021, as a result of collective bargaining and transparency measures. In contrast, the pay gap in the UK, where a quarter of workers belong to a union, stands at 9.4%; in the US, where about 1 in 10 workers are unionized, it’s 16.3%.

In many countries, companies are obliged to publish their gender pay gaps every year but don’t face any consequences if they don’t reduce it. That’s why legislation around enforcement is needed.

Iceland was the first country in the world to introduce a policy in 2018 that requires companies and institutions with more than 25 employees to prove that they pay men and women equally for a job of equal value, shifting the burden of proof to the employer. Those failing to comply incur a daily fine of $500. The pioneering measure has contributed to the country halving its gender pay gap in the past decade.

Equal pay is not merely a workplace issue – it’s a societal imperative and demands systemic action. Feminist movements, labour unions, employers, policymakers and society at large all share a collective responsibility to dismantle the barriers to gender equality in the workplace and close the gap by 2030.