Counting Women, Counting Progress: Why Gender Data Will Make or Break the SDGs

UNGA 80, Five Years Left

As world leaders gather for the 80th UN General Assembly (UNGA 80) this September, the global community marks ten years since adopting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This should be a moment of celebration, but instead it is a moment of reckoning. With just five years left to deliver on the 2030 Agenda, progress is far off track: less than 20% of SDG targets are projected to be achieved by the deadline.

Failure to act on gender equality is impeding progress. Our research shows that 74% of SDG targets will not be achieved without gender equality, yet 40% of countries are stagnating or even regressing on women’s rights.

Progress depends on measurement. Timely, disaggregated, and inclusive gender data is essential to delivering on the SDGs’ core promise to leave no one behind. Encouragingly, recent years show that when investments are made, progress follows. More countries now collect labour force data that better captures women’s participation in paid and unpaid work; time-use surveys are increasingly widespread; and coverage of legal frameworks related to gender equality has expanded. These gains prove that progress is possible, but they remain the exception, not the norm. As we pass the two-thirds mark towards 2030, the lack of comprehensive and timely gender data is still one of the biggest barriers to achieving the SDGs.

Measuring Inequality: The Case for Disaggregated Data

There has been progress towards disaggregating data. Since 2019, 61% of countries have made ‘fast progress’ towards producing more disaggregated statistics (measured by SDG indicator 17.18.1). But these gains are uneven. Open Data Watch’s Gender Data Compass shows that national budgets for data remain low, capacity shortfalls persist, and in many cases funding has declined since the pandemic. Crucially, ‘progress’ on this SDG indicator is measured by a country’s capacity to produce disaggregated data across multiple characteristics, yet in practice, most countries only manage the simplest disaggregation, by sex.

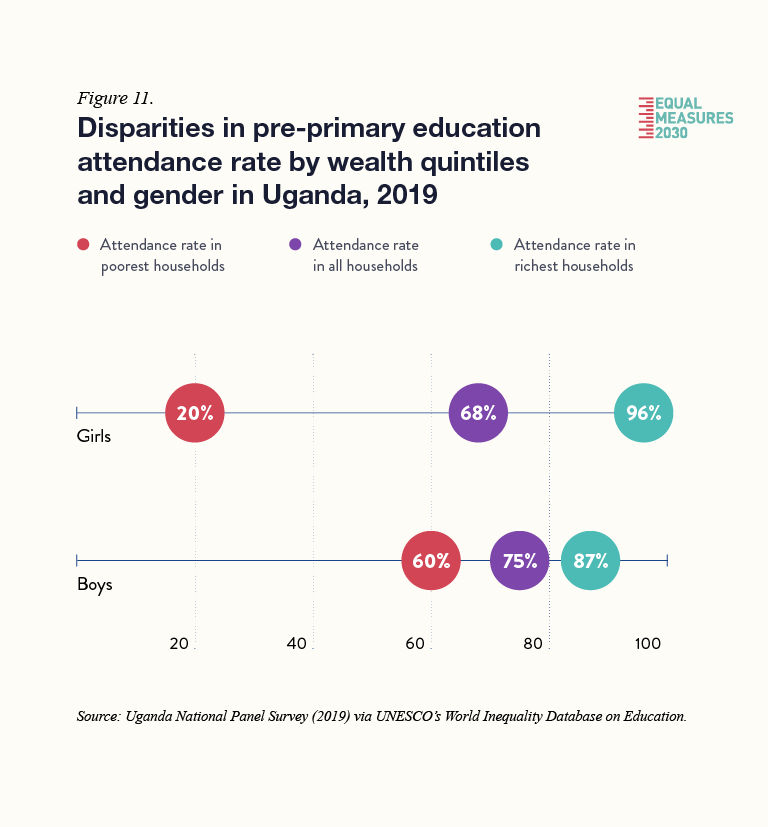

National averages are often misleading. Disaggregated data, broken down by gender, age, disability, geography, and wealth, reveals inequalities that otherwise remain invisible. The SDG Gender Index illustrates this vividly in Uganda. In the overall picture for education in 2019, 68% of young girls participated in pre-primary education, in the year before starting primary school, compared to 75% of boys. However, when the data is disaggregated by household wealth, a different picture emerges: among the poorest families, only 20% of girls attended pre-primary education, compared to 60% of boys.

Without disaggregated data, these girls remain unseen. Education policies risk being designed for an “average child” who in reality reflects only the least disadvantaged. What appears as progress at the national level masks failure to reach the very children the SDGs pledged to prioritize.

Disaggregated data is therefore not just technical: it is about power. It determines whose lives are visible, whose struggles are acknowledged, and whose needs shape policy. As Equal Measures 2030 has argued, advancing data feminism means challenging the power imbalances embedded in what is measured, who collects data, and how it is used. Unless we shift this dynamic, the SDGs risk reproducing the very inequalities they were designed to end.

The Importance of Citizen Data in a Fragile Global System

According to the UN Women Gender Snapshot 2025, global data availability on SDG 5 indicators has improved to 57.4 percent —a welcome gain, but it still means that 43 percent of the data needed to track gender equality is missing. Across the 2030 Agenda, almost 70 percent of SDG indicators now have good overall coverage. However, the trend coverage for goals such as SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) is still below 30% according to UNSD. These gaps leave critical blind spots for monitoring progress and designing evidence-based policies as 2030 draws near.

The challenge is not only technical but political. The closure of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program in early 2025 dealt a major blow to global gender data. For nearly four decades DHS was a cornerstone of health and gender statistics, covering more than 90 countries and informing decisions on family planning, maternal health, and HIV prevention. Since 2015, DHS has provided 70 percent of global data points on contraceptive use (SDG 5.6.1) and experiences of sexual violence (SDG 16.2.3), and more than 50 percent on female genital mutilation (SDG 5.3.2). The program’s termination reflects not just funding shortfalls but also a shrinking civic space and growing political unease with independent, credible data that can expose inequality or challenge official narratives.

However, at the same time, grassroots movements are showing what inclusive, innovative data systems can achieve. In Kenya, GROOTS Kenya, a coalition of more than 2,500 women-led community groups, successfully pushed the Kenya Bureau of Statistics to integrate their citizen-generated data into the Women’s Empowerment Index and County Poverty Profiles. This recognition shifted power dynamics. Women at the grassroots were no longer just data users, but data producers whose evidence reshaped national policy.

The contrast is stark. While global systems are under threat, citizen-generated data is pushing boundaries, proving that better, more inclusive data is possible. The path forward is not simply more data, but better data: timely, comparable, disaggregated, and rooted in the lived realities of women and girls.

Call to Action: Closing the Gender Data Gap

UNGA 80 must mark a turning point on gender data. The priorities are clear:

- Invest in national and global statistical systems. In India, investment in Time Use Surveys has led to data that sparked debate and reforms around women’s ‘time poverty,’ shaping labour and care policies.

- Recognize and integrate citizen-generated data into official frameworks, following the success of GROOTS Kenya.

- Prioritize the most marginalised groups. In Latin America and the Carribean, UN Women’s “Gender Equality Observatory” disaggregates data by age and ethnicity, making visible the situation of Indigenous women who were previously excluded from official policy debates.

- Ensure open, accessible data, such as Kenya’s Open Data Initiative, which makes gender indicators publicly available, enabling civil society to monitor county-level progress and advocate for investments.

- Advance data feminism by rethinking power in data collection. In South Korea, repeated national surveys on unpaid care work highlighted gender imbalances in time use. This informed reforms expanding parental leave and policies to encourage men’s participation in care.

Where targeted investments are made, results follow. Gender data, when used well, can drive smarter policies and stronger outcomes.

Conclusion: Counting Everyone Makes Sure That Everyone Counts

The SDGs cannot succeed without closing the gender data gap. With only five years left until 2030, waiting decades for complete gender data is not only unacceptable, it is a betrayal of the promise to leave no one behind.

A girl born today should not have to wait until well beyond her lifetime to live in a world of equality. UNGA 80 is a milestone moment: leaders must act now to ensure data systems are inclusive, open, disaggregated, and feminist. Without gender-responsive data, governments and partners will be unable to track real progress and identify who is being left behind.