What does the future hold for women under Guatemala’s new government?

Written by Ester Pinheiro, Communications Officer, Equal Measures 2030

Governments in Central America have not always been at the forefront of promoting institutional policy changes to address gender inequalities. One of the main reasons is the lack of female representation in politics in some countries in the region and the lack of progressive parties not associated with corruption that advance the rights agenda. However, Guatemala inaugurated its new president on January 15th 2023, with a gender-equal cabinet and a promise to fight corruption. What could this new government hold for women and girls in Guatemala?

Guatemala’s presidential elections in 2023 sought a different government that could change the reality of kleptocracy and violence that suffocates women and girls. Bernardo Arevalo of the progressive social democratic Movimiento Semilla party managed to get enough votes to compete for the country’s presidency against Sandra Torres of the National Unity of Hope, and thus go all the way to the second round on the 20th of August, winning with more than 60% of the almost 4 million electoral votes.

Is more women in politics always a solution?

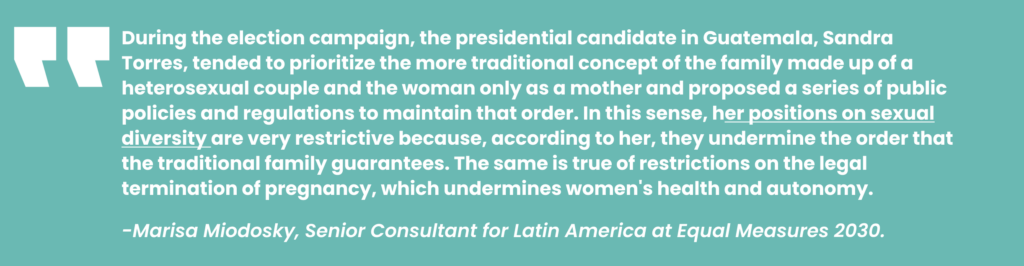

The proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments in Latin America is considered “very low”, according to the 2022 SDG Gender Index. Guatemala scores 21 points below the already very low average for the region. But being a woman does not necessarily make you a progressive candidate, as is the case with Sandra Torres in Guatemala, explains Marisa Miodosky, Senior Consultant for Latin America at Equal Measures 2030.

The presence of these women with a reactionary agenda does not guarantee the struggle and protection of rights for gender equality and women’s autonomy. Many of the women who reach positions of power representing right-wing or far-right parties subscribe to an anti-feminist and anti-rights discourse in relation to abortion, immigration and LGBTQIA+ issues.

This is a global reality with examples such as Nikki Haley, potential presidential candidate of the Republican party in the US, Marine le Pen in France, Giorgia Meloni, Italian prime minister and Keiko Fujimori in her bid for the presidency in Peru. In the UK, some of the most aggressive anti-immigration politics have been voiced by women of color such as Priti Patel, Suella Braverman and Kemi Badenoch, a black woman who has called herself an anti-woke culture warrior.

In Argentina, the recently elected Milei government, with a ⅓ of women in the cabinet, did not hesitate to dismantle the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity and send to congress a compendium of laws that seek to change the rules of cohabitation in Argentina with serious effects on the care system and electoral parity, among others. “While some of their legislators are against laws that prevent and punish different types of violence such as street harassment,” says Marisa.

On the contrary, there is a pressing need for a government crafted by and tailored to the diverse experiences of women, facilitating their democratic representation. Unfortunately, this was not the case for the candidate Maya Mam Thelma Cabrera, whose expertise and experience lies in the Indigenous context. Thelma, along with her former deputy, the human rights ombudsman Jordán Rodas, ran under the banner of the Movement for the Liberation of the Peoples (MLP), an Indigenous party with a substantial departmental structure, but were unable to participate.

“Thelma is a community leader with a great deal of influence gained collectively, not just personally and egocentrically like others,” says Ángela Chiquin Chitay, a young indigenous Guatemalan founder of the Kemok organization. According to her, Thelma has been able to manage her resources despite not having the same privileges as others. “She was not self-proclaimed; it was the deputies and mayoral candidates with a registered committee who chose her to participate and represent the political tool.”

Corruption and the rights agenda

With politics marked by a ‘corrupt pact’ (‘pacto de corruptos’ as it is popularly known in Guatemala for the alliance between judges, congressmen, businessmen and different actors who co-opt and plunder the state), it is difficult to guarantee the rights of the population, especially the rights of women and girls.

Danessa Luna, Guatemalan activist and women’s human rights defender at Asogen, one of our coalition members, shares that the corrupt pact has tried to put an end to the advances in women’s rights, particularly to put an end to the institutional framework for women that has taken 30 years to build, and to tear back progress made on important issues such as sexual and reproductive health and rights.

There is an institutional crisis in Guatemala with a traditional-conservative positioning that has co-opted the institutions, mainly the three branches of government (executive, legislative and judicial) and other autonomous institutions that are key to the functioning of the rule of law, such as the University of San Carlos, the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office, the Constitutional Court, the Bar Association, among others.

The kleptocracy in the state threatens years of looting in the country, corruption and impunity, as well as drug trafficking, which also weakens democracy, institutions and women’s rights. “There are politicians involved in drug trafficking and control of the drugs that pass through Guatemala, and this is also a powerful reason why many of them want things to continue as they have been,” says Danessa. This system also establishes a regime of persecution of any student, gender equality advocate, judge, prosecutor or journalist who denounces illegalities and gender-based violence.

Will Semilla take power in Guatemala?

Fearing the loss of government power and the whimsical management of the treasury, the “pact of the corrupt” led the political system in Guatemala to reject the participation of opponents who might risk their interests and allow the candidacy of other political actors with serious accusations.

This same pact led to an attempted coup d’état in Guatemala in December last year and this year as Arevalo tried to enter office. The country’s Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) asked to declare the electoral results null and void. However, the Superior Electoral Tribunal clarified that the elections will not be repeated. Even the OAS has condemned the coup attempt in Guatemala. This was all due to the “Corrupción Semilla” case being investigated by the winning party along with new requests for impeachment against president-elect Bernardo Arevalo and Movimiento Semilla deputies Ligia Hernández and Samuel Pérez.

They want to impose for the public record that there was fraud, that Semilla is an illegally formed party and that the MP’s actions are to “guarantee the citizen’s vote”. However, for Danessa, there was no fraud, but rather that the population is more informed and critical of the flow of information. “They have interfered with the wrong generation”. For the gender leader, President-elect Bernardo Arevalo, did a good job with the population, “above all a painstaking task, sharing his anti-corruption, anti-impunity approach to tackle what has left the population without health, without education, without security, without anything”.

What is expected from Bernardo Arevalo’s government?

Feminists and women’s organizations view the Movimiento Semilla as positive and hopeful.

For girls and women, it is hoped that there will come times of respect for their rights, of having a more equitable government that has thought about their rights, such as access to justice, education, health and other specific rights. It is hoped that there will be greater possibilities to negotiate, to dialogue and to have the possibility of governing together, to be heard and to be visible.